Camille Pissarro’s lifelong interest in the human condition is unique among Impressionist landscape painters. From his early years in the Caribbean and Venezuela until his death in Paris in 1903, he produced a vast oeuvre of drawn, painted, and printed figures. He was also a committed reader of radical social, political, and economic theory, including the writings of the French proto-anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, friends such as Jean Grave and Élisée Reclus, and the great anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin.

Many examinations of Pissarro have treated his politics and his art as separate categories, refusing to explore the most basic connections. This volume, authored by noted Pissarro expert Richard R. Brettell, is the first truly to bridge that gap. Key to this investigation of the painter’s humanism is Pissarro’s identity as a member of a diasporic Sephardic Jewish family—a complex constellation of individuals living and working in Uruguay and Venezuela, France and England, and the United States during the artist’s lifetime.

Demonstrating that Pissarro was in every sense a family man, Brettell addresses the artist’s portraits of family members alongside pictures of artists, neighbors, domestic help, rural workers, and various other associates. Linking Pissarro’s web of family and friends to his radical social and economic ideals, the project breaks new ground in reconsidering the artist’s figural works.

He became deeply immersed in revolutionary politics, specifically in

anarchist thinking that espoused a radically egalitarian,

anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian society. Partly because this way of

life was most easily realized in a rural setting, Pissarro moved to

Pontoise, a farming village outside Paris. The result, in painting after

painting, was a vision of the world as a kind of extended family, or

kinship network, with larger circles of relationships rippling outward

from Pissarro’s own domestic unit. Pissarro’s idealism was insistent.

Because he wanted his projection of a better future to be realized, he

tried to work it out in the present, through his own practice of ethical

generosity, firm in the face of political censorship (he was closely

watched by the French police because of his anarchist ties),

anti-Semitism (he forgave this in Degas) and professional isolation as

an artist who was neither born French nor had French citizenship (a

status he shared with his friend Mary Cassatt). Yet the stranger in him,

the foreigner looking in, led him to acknowledge the underside of that

vision. In late 1880s he made a series of 30 ink drawings illustrating

the brutalities of urban capitalist society. The album, titled

“Turpitudes Sociales” (“Social Disgraces”), have the bold, crude look of

newspaper cartoons and were made for two of his nieces by way of

political instruction. Nothing else by him is like them, and they

haven’t been exhibited in a museum until now. - HOLLAND COTTER

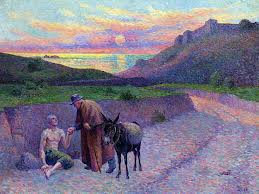

In the mid-1860s Pissarro lived in the village of La Roche-Guyon, where he painted this scene along the River Seine. A bourgeois woman attends to her two well-dressed children as they enjoy a donkey ride while a pair of vagabond children, dressed in rags, look on.

"Capital," from Turpitudes sociales, 1889–90.

"The Hanged Millionaire," from Turpitudes sociales, 1889–90.

The Marketplace MARKETING

THE MARKETS - Pissarro’s representations of rural food markets can be

understood as a metaphor for his own marketing of art. In the late

nineteenth century, works of art were typically associated with luxury

and leisure, commodities accessible only to the wealthy. Pissarro and

other left-wing artists held a different view: the very life of the

artist was a liberation from the bourgeois preoccupation with money or

capital. Artists could live simply and produce art that could decorate

and enhance ordinary life.

MARKETING

THE MARKETS - Pissarro’s representations of rural food markets can be

understood as a metaphor for his own marketing of art. In the late

nineteenth century, works of art were typically associated with luxury

and leisure, commodities accessible only to the wealthy. Pissarro and

other left-wing artists held a different view: the very life of the

artist was a liberation from the bourgeois preoccupation with money or

capital. Artists could live simply and produce art that could decorate

and enhance ordinary life.

PISSARRO'S PEOPLE

In the mid-1860s Pissarro lived in the village of La Roche-Guyon, where he painted this scene along the River Seine. A bourgeois woman attends to her two well-dressed children as they enjoy a donkey ride while a pair of vagabond children, dressed in rags, look on.

"Capital," from Turpitudes sociales, 1889–90.

"The Hanged Millionaire," from Turpitudes sociales, 1889–90.

The Marketplace

MARKETING

THE MARKETS - Pissarro’s representations of rural food markets can be

understood as a metaphor for his own marketing of art. In the late

nineteenth century, works of art were typically associated with luxury

and leisure, commodities accessible only to the wealthy. Pissarro and

other left-wing artists held a different view: the very life of the

artist was a liberation from the bourgeois preoccupation with money or

capital. Artists could live simply and produce art that could decorate

and enhance ordinary life.

MARKETING

THE MARKETS - Pissarro’s representations of rural food markets can be

understood as a metaphor for his own marketing of art. In the late

nineteenth century, works of art were typically associated with luxury

and leisure, commodities accessible only to the wealthy. Pissarro and

other left-wing artists held a different view: the very life of the

artist was a liberation from the bourgeois preoccupation with money or

capital. Artists could live simply and produce art that could decorate

and enhance ordinary life. PISSARRO'S PEOPLE